Description

of the Passages Performance

Project

[ Quick links: Home - A0 - A1

- A2

- A3

- A4 -

A5 - A6 - B0

- B1

- B2

-

B3

- B4

- B5

- B6

- B7

- B8 - B9

- B10

- B11

- B12

- B13

- B14 - B15 - B16 -

C1

]

The

performance

project, entitled Passages,

was designed to give

opportunities to test and refine the Theolux control interface in use,

as well as to investigate the strategic interventions developed in

chapters II.1 and II.2, with myself in the role of Lighting Artist. The

performance was both rehearsed and presented in a black-box studio

space at Rose Bruford College during July and early August 2009. The

three actors and the Design Associate were students on the MA Theatre

Practices programme at Rose Bruford College, while the director was a

professional employed for the project. (I am using the term ‘actor’

here to refer to the three on-stage performers. I use the term

‘performer’ as an inclusive term, covering both the actors and myself

as the lighting artist.) The Associate

Director was

an undergraduate Directing student, and technical and organisational

roles were filled by Rose Bruford staff and students. The director also

created and operated the music and sound score. Further details of the

company can be found in appendix B15.

Passages took as its theme and

source material the work, ideas and –

particularly – the death-story of the German-Jewish philosopher and

critic Walter Benjamin, who died in a hotel room on the Franco-Spanish

border in 1940 while fleeing from the Gestapo. I took an early decision

in planning the performance project that it should be developed through

a devising process rather than based on an extant dramatic text, in

order to maximise the potential input of the lighting artist in the

creative development of the work. Specifically, the performance would

be developed through a devising process involving the director, actors,

myself as lighting artist, and other members of the company, and this

process would lead to the making of a performance ‘text’ that was fixed

at the macro scale, while allowing for small, local variations of

timing or expression from performance to performance. Such fixing of

the performance was important in research terms, since my thetic

project concerns the rehearsal and live performance of lighting, not

its improvisation (a matter I return to in chapter III.2). My concern

here is with the subtleties of expression that can take place as

audience, performers and light interact and respond to each other: a

focus in the moment of performance not on ‘what happens’ (which has

been pre-agreed) but on ‘how it happens’.

It was also in

my view important that the material chosen as a starting

point was sufficiently rich in the kind of dramatic possibilities that

would lead towards a performance style not determined by an adherence

to what we might loosely call ‘realism’. This avoidance of a purely

representational style was intended to ensure scope for light to take

on a full role as a major expressive element of the performance.

Benjamin’s death story in my view offers dramatic potential, not least

because the exact circumstances are unclear and contested. In addition,

his writings and ideas contain metaphors and allegories that are

theatrically suggestive as well as offering significant challenges when

attempting to use them as the basis for a theatre performance. An

influential book for the director Chris Goode and myself during the

early development of the project (prior to the other company members

becoming involved) was Walter

Benjamin's Archive (Marx 2007), which

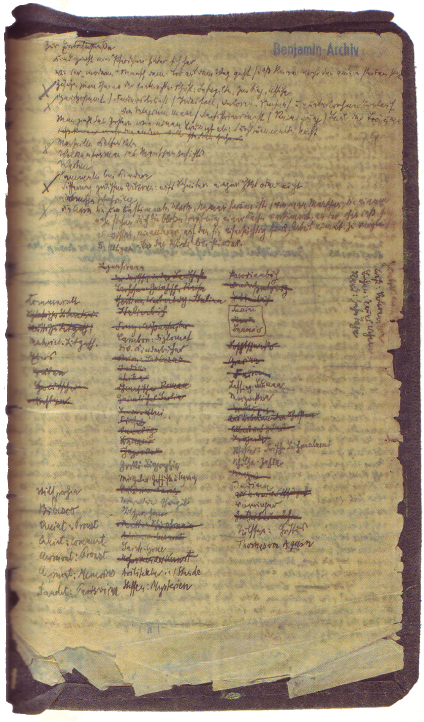

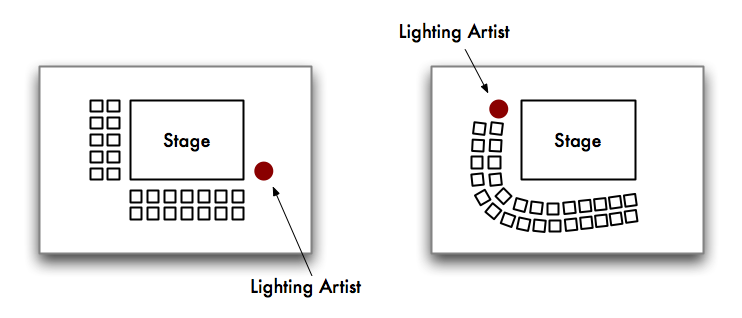

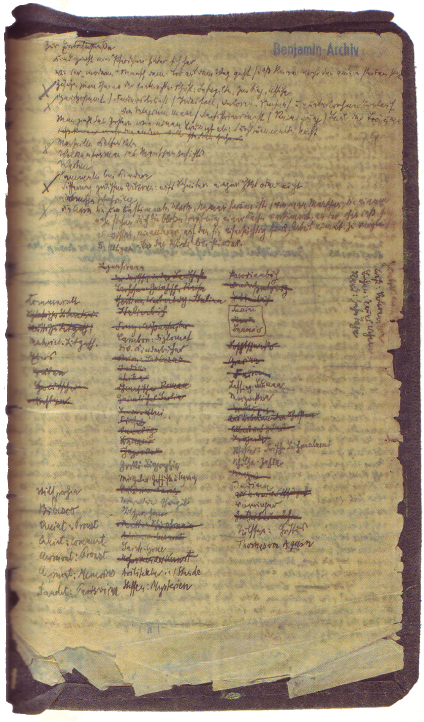

contains facsimile pages of Benjamin’s writings. What I judged to be

the potent visual qualities of the paper, along with Benjamin’s

handwriting and use of page space, gave me confidence that we could

together find ways of communicating aspects of Benjamin’s cerebral life

and work through the material substance of a theatre performance (see

image below). Some of the paper and writing textures were used very

directly in the scenic design for Passages,

as

well

as

fuelling

the

devising

process.

Having

identified the source material and an overall way of working,

the Director and I established a structure and schedule for the

process. An initial meeting of the company introduced the source

material, and was followed by a two-week period for reflection and

further research, as well as technical preparation of the studio space.

Fourteen days of rehearsals were spread over four and a half weeks,

allowing company members time for various other commitments, as well as

reflection and independent work on the project. As lighting artist, I

was present in the rehearsal room throughout every rehearsal day with

Theolux and a lighting rig set up, in line with my Strategic

Intervention that the lighting artist should rehearse with the other

performers. Because we were rehearsing and performing in the same

space, we did not have the conventional theatre distinction between

‘rehearsal’ (rehearsal in a rehearsal room without technical and

scenographic apparatuses) and ‘production’ (rehearsal in the

performance space with technical and scenographic apparatuses). Thus we

did not distinguish technical or dress rehearsals as such, but moved

incrementally from relatively unstructured development of performance

material to the rehearsal of an emergent performance script in

increasingly structured and formalised ways. This structuring was

shaped particularly by the Director, who organised the material into a

series of sections that could be rehearsed as freestanding sequences.

Some

sections foregrounded lighting or sound, and each section

gradually acquired its own aesthetic and dramatic tone. As with the

lighting, the scenic, costume and sonic elements were introduced,

experimented with, developed and refined gradually throughout the

rehearsal period, and with the involvement of all of the members of the

company. The time between the rehearsal days allowed technical work in

the studio space to be undertaken. On the final day of rehearsals we

ran the piece several times in a simulation of performance conditions,

including one run with a small invited audience. On the performance

day, we ran through the piece in the morning, with the performance for

examiners and invited academics and professionals (selected for their

ability to offer feedback from diverse perspectives through the

post-performance discussion and individual correspondence) in the

afternoon. An evening performance accommodated Rose Bruford staff and

students, as well as guests of the company, and gave an additional

opportunity for feedback through a second post-performance discussion.

The black-box

studio space used for the performance has no fixed

seating arrangement or technical control area; it consists of a space

approximately thirteen metres by nine, with a height of nearly four

metres to the lighting grid, and entrance doors and doors to a

technical service and storage area at either end of one of the long

walls (see appendix B10

for images of the studio space). No decision

was made to begin with about the size or orientation of the performance

area within the overall space, or its relationship with the audience

seating, although we were aware that my Strategic Intervention

regarding the geometry of the performance space would be an important

factor when deciding on the room’s spatial configuration. I wanted to

begin the rehearsal process without pre-conceived ideas about the use

of space other than the Strategic Intervention, or rather, given that

even an empty room cannot be neutral, I wanted initially to resist

making such decisions until the nature of the performance we were

making had begun to emerge. (The non-neutrality of an empty room is

perhaps analogous to the non-neutrality of an empty canvas. In

Deleuze’s terms, which I introduce in chapter II.1, an empty room can

be seen as being ‘already invested virtually with all kinds of

clichés’ (Deleuze 2005, 8). That the studio space used for Passages has a major and a minor

axis of symmetry, and has an entrance door near one corner, is enough

to begin to shape how people occupy and use the space, according to

socially and culturally conditioned habits.)

Two early decisions began to shape

our use of the studio space – one directly related to the material we

were working on and the other more pragmatic. Firstly, the Director

Chris Goode proposed that the stage space should represent the hotel

room in which Benjamin died (though this mimetic location would not be

taken literally during all of the performance). Secondly, the Theolux

console had to be set up in the space, and since it is designed to be

moveable rather than portable, we had to choose a single location for

at least the first phase of rehearsals. I chose to set it up toward one

corner of the studio, diagonally opposite the entrance door, so as not

to be in the way of people and equipment entering the room, while

having a good view of activities anywhere in the space.

Prior to the

first rehearsal day, an initial lighting configuration was

set up in the studio, intended to offer the ‘randomised palette’ of my

first Strategic Intervention. Strictly, this initial set up was not

random (as might be achieved through some stochastic process to

determine the type, position, focus and colour of each light), but it

was disconnected from the specifics of the yet-to-be-determined

performance. Thus in choosing a series of lighting elements with the

potential to create certain affects, I was motivated by a sense of what

might be interesting or useful, rather than designing with a specific

need and a specific performance moment in mind. For example, the colour

palette comprised a wide range of colours, including some quite

saturated ones, but all the colours I selected had a quality in common:

they were all impure, ‘unclean’ tones. This general choice was a

response to the strong feeling I had from the source material of the

past brought into the present, of something distant brought close, as

an old photograph can sometimes do. The impure colours have – at least

for me – a comparable effect. However, I made no decisions (and indeed

was careful to avoid, at least consciously, making decisions) about how

and when in the performance the colour palette would be used. Thus the

initial lighting set-up offered us in the first few days of rehearsal a

palette of lighting gestures with the potential to produce a range of

lighting affects, to ‘seed’ the process of lighting through rehearsals

and into performance.

One of the

difficulties of lighting through the rehearsal process

is that, whilst Theolux was designed to allow lighting to be performed,

with the lighting artist responding in the moment, the lighting rig

itself does not offer that flexibility. (The use of automated lights

would to some extent solve this problem, since they can be refocused

and coloured remotely from the lighting console. However, the large

number of controllable parameters involved brings its own difficulties,

both technically in designing the console, and in creating a control

interface with the kind of immediacy of action that I was seeking.

Early on in my research, I decided not to work with automated lights

for these reasons.) In planning the rehearsal

schedule and process, we made several decisions to help ameliorate this

difficulty. Firstly, we set a deadline of the end of the fourth day of

rehearsal to decide on the spatial configuration of the performance

area and the audience within the overall studio space. Once this

decision was made, future rigging, focusing and colouring of lights

would be undertaken in the knowledge of the spatial layout that would

be used in the final performance, so that no wholesale re-rigging would

be required after that point. Secondly, having the rehearsal days

spaced out with technical time in-between meant that the Lighting

Manager and her team could make any changes I requested before the next

day of rehearsal. Thirdly, one of the lighting team was present

throughout most of each of the rehearsal days, so I could request small

changes (refocusing a light, or changing a colour) immediately, with

minimal disruption of the rehearsal. Working in a studio space with

easy ladder access to the lighting grid was helpful in this respect.

The spatial

configuration we decided upon had a performance area

approximately four meters by three placed near the middle of the

studio, offset towards one long wall. The relatively small size of the

performance area was intended both to establish the hotel room at a

realistically human scale, and to ensure that the lighting process did

not become impeded by the need to use multiple fixtures to light a

large area, thus occupying crew time and technical resources that would

be better deployed in responding to the emerging needs of the piece as

the rehearsals progressed. Initially, the audience was placed facing

two sides of the performance area, with the Theolux console and the

Lighting Artist located at one corner of the performance area, at the

end of the longer block of seating and opposite the shorter block. (The

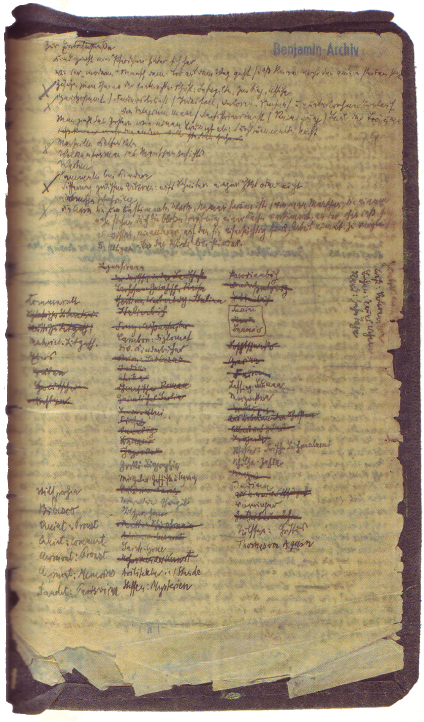

following diagram shows the original (left) and

final (right) seating configurations.)

My intention

with this arrangement was to ensure that I as lighting

artist could see both the actors and the audience, and they could see

me. The location – at the end of a block of seating, but also adjacent

to an area that might be seen as ‘offstage’ or even ‘backstage’ – was

intended to set up an ambivalence between the lighting artist as

spectator and the lighting artist as performer/operator. This is the

ambivalence identified by Iain Mackinosh, with which I begin chapter

II.2 and that I intended as a way of allowing myself as lighting artist

to join the ‘circuit of energy’ between actors and audience.

This initial

configuration was revised following a visit to rehearsals

of my Director of Studies and other guests, who provided some useful

feedback on their experience of the spatial set-up. After some

experimentation, led by myself but with the involvement of other

company members, we arrived at a modified configuration that became the

final one used for the last few days of rehearsals and into

performance. This altered set-up retained the rectangular performance

space representing the hotel room, but wrapped the audience around it

in a single arc of seating (shown in the diagram above). The change was

motivated by several perceived benefits. Firstly, it addressed one

aspect of the feedback from my Director of Studies by giving slightly

more distance between audience and actors, while retaining a strong

sense of intimacy, promoting (in my view) the kind of balance between

engagement and critical distance I identify in chapter II.2 as the

interrogating gaze. Secondly, the new configuration united what had

previously been two blocks of seating into a single arc of seats,

eliminating the possibility of the audience perceiving itself to be in

two parts, and so perhaps disrupting the ‘circuit of energy’. Thirdly,

the ‘arc wrapped around a rectangle’ hinted at the kinds of theatre

geometries identified by Mackintosh (1993, 161 onwards), without

slavishly adopting the precise Euclidean geometries of classical

architecture.

As part of this reconfiguration, the Theolux console was

moved to the diagonally opposite corner of the performance space from

its initial position. This placement, still at the end of the rows of

seating and so retaining its ambivalence, brought the lighting artist

nearer to the centre of their field of view for a greater proportion of

spectators, further (I supposed) promoting the circuit of energy, and

also placed the Theolux console near the door through which the

audience entered and left the space, allowing them to observe it

briefly and so boosting its prominence within the audience’s overall

experience of the event. Arguably, in terms of my earlier observation

with regard to research ‘ownership’, this shift pointed to my own

intervention as being rather more determining in terms of what

spectators experienced ‘in the event’.

The three actors

were all dressed as Walter Benjamin, although the

costumes were indicative rather than historically accurate, in

accordance with our overall approach of being suggestive rather than

realistic. The set design emerged during the rehearsal period,

beginning with some basic furniture for the hotel room: a bed, a small

drop-leaf table (used also as a writing desk), two chairs and a stool.

Through the development and devising process, we decided that we wanted

to introduce paper and writing in a variety of textures and qualities,

together with a motif of clocks set to different times, intended to

suggest travel and time-zones. By the end of the rehearsal process,

various types of brown and tracing paper, printed with Benjamin’s

characteristic handwriting and textures from old maps, were used on the

floor in the corners of the stage space to help delineate the room

boundaries, as well as providing the material for the construction of a

large ‘map’ during the performance. The clock motif appeared in the

form of three framed pictures of clocks, each showing a different time

and suspended where the rear and side walls of the hotel room would be.

We made no attempt to hide the studio space beyond the hotel room, and

indeed we retained as a scenic element all of the paperwork that had

been generated during the rehearsals and placed on the studio walls.

Rehearsals,

performances and post-performance discussions were videoed

throughout in order to capture the process for later analysis. Some of this video material is

contained in appendices B2, B3,

B5,

B6,

B7).